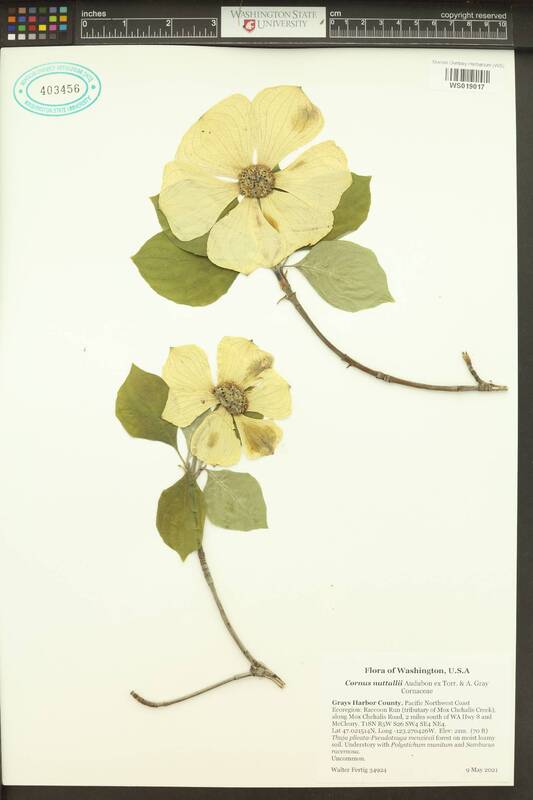

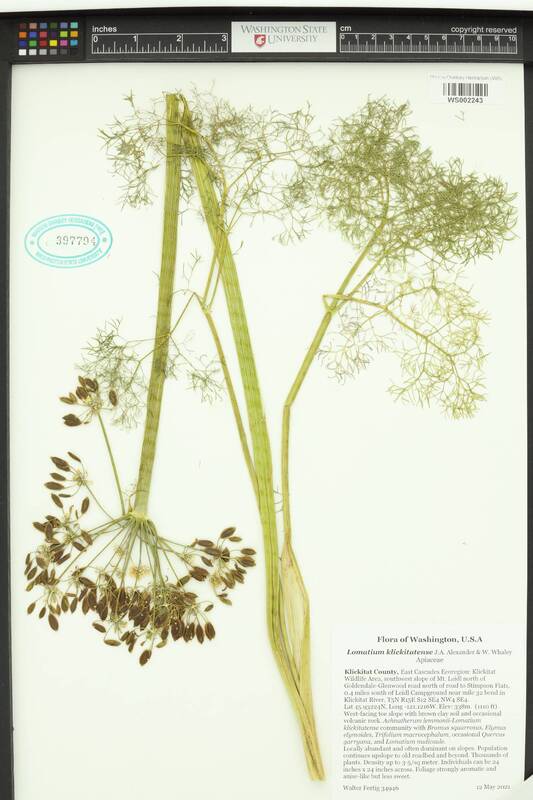

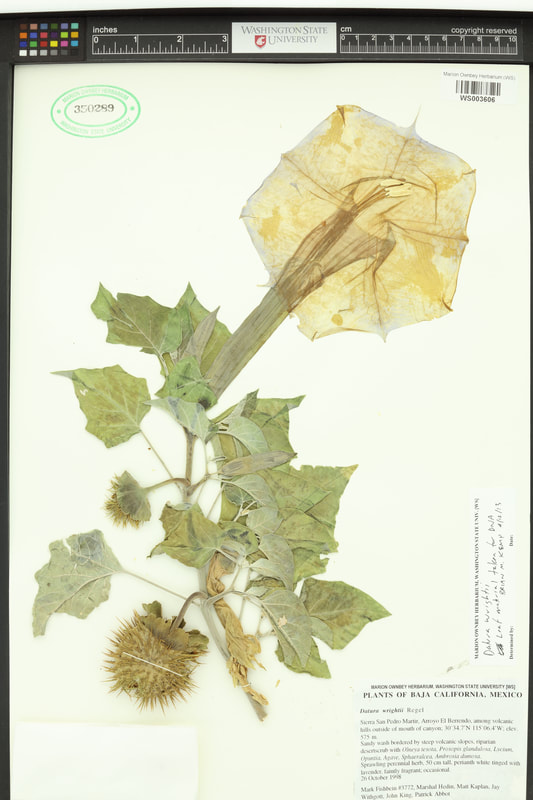

Speaking of Specimens: Tales from the Marion Ownbey Herbarium, Washington State University.4/17/2024 4. Pacific dogwood (Cornus nuttallii) How many flowers do you see on each of these branches of Pacific dogwood? If you answered “one” on each stem, don’t feel too bad. Most people would agree with you. Of course, you would all be wrong. The correct answer, to use the technical botanical term, is “lots”. Each dogwood flower is actually a ball-like inflorescence of several dozen tiny, 4-petaled, greenish-white to purplish flowers surrounded by 4-7 large, whitish, petal-like bracts (technically leaves) that create the illusion of a single flower. The petals on dogwood are analogous to the red “petals” of a Christmas poinsettia, though these are leaves too. Pacific dogwood is closely related to the flowering dogwood (C. florida) of the eastern United States. Early botanical explorers in the northwest, including Meriwether Lewis and David Douglas, assumed the showy trees were one and the same species. Thomas Nuttall was the first scientifically trained botanist to note the difference (C. florida has only 4 petal-like bracts and fruits that are round, rather than angular in cross-section). Nuttall was a contemporary of John James Audubon and sent a sprig of Pacific dogwood and some bird skins to his artist friend as a gift. Audubon scooped Nuttall and published Cornus nuttallii as a new species – having the decency to at least name it after Nuttall. This was the first and only plant species ever scientifically described by Audubon. True to its common name, Pacific dogwood ranges mostly near the Pacific Ocean from southwestern British Columbia and western Washington, south through Oregon to southern California. Nearly all populations are found in and west of the Cascade Range. Some isolated populations are disjunct in the Selway-Lochsa river drainage of northern Idaho, where rainfall and temperature patterns locally mimic the wet northwest coast. Nearly 100 “coastal disjunct” plant species show a similar geographic pattern in Idaho, raising the question of whether these species have persisted following post-glacial climate changes in the intervening areas, or arrived from long distance dispersal. For more information on the Ownbey Herbarium and its specimens, go to https://ownbeyherbarium.weebly.com/ – Walter Fertig, collections manager, Marion Ownbey Herbarium. 3. Klickitat biscuitroot (Lomatium klickitatense) Sometimes insects make pretty good taxonomists. At least that is what entomologist Wayne Whaley discovered when examining the favorite host plants of Indra swallowtail butterfly caterpillars. Across the western US, Whaley observed Papilo indra caterpillars feeding on some, but not all, populations of the widespread umbel species, Gray’s biscuitroot (Lomatium grayii). Systematist Jason Alexander of the Jepson Herbarium undertook a detailed analysis of hundreds of specimens of L. grayii across its range and discovered consistent morphological differences that correlated with geography and the feeding habits of Indra caterpillars. A companion study also found consistent differences in the essential oils present in the foliage of these different populations. In 2018, Alexander, Whaley, and Natalie Blain published a paper splitting L. grayii into four species: L. papilioniferum (for the Indra butterfly) of the Pacific Northwest, L. depauperatum (endemic to Utah and Nevada), L. grayii proper (now restricted to SE Idaho, E Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming) and L. klickitatense, endemic to the Klickitat River drainage and vicinity in southern Washington and adjacent Oregon. Klickitat biscuitroot (L. klickitatense) differs from the more widespread L. papilioniferum in being much more robust (with leaves and stems up to 3 feet tall and wide) and having more finely divided leaves with long, narrow leaflets that are smooth, rather than rough (scabrous). It is locally abundant within its narrow range and easy to spot along the red cliffs on the Goldendale-Glenwood Highway and Highway 142 along the Klickitat River. Ironically, this species does not appear to have ever been collected by Wilhelm Suksdorf, Washington’s preeminent pioneer botanist and longtime resident of nearby Bingen in the Columbia Gorge. Over a dozen collections of L. klickitatense were made in the 1960s and 1980s (including many by a WSU graduate student studying chemical properties of Lomatium species), but it remained undetected in the herbarium folders. What other unnamed species may be lurking in the cabinets? For more information on the Ownbey Herbarium and its specimens, go to https://ownbeyherbarium.weebly.com/ – Walter Fertig, collections manager, Marion Ownbey Herbarium. 2. Indian apple or sacred datura (Datura wrightii) The genus Datura contains about 25 species found worldwide in tropical and warm temperate areas, including North America. Like many members of the nightshade family (Solanaceae), Datura species are deadly poisonous, though they were used (carefully) by indigenous cultures as a narcotic and to induce hallucinations. All parts of the plant (leaves, stems, fruits, flowers, and even nectar and pollen) contain various alkaloids, such as atropine, hyoscyamine, and scopalomine. Naturalists have observed hawkmoths and hummingbirds behaving erratically around Datura flowers, perhaps as a result of intoxication from these compounds. Pollinators may become “Jimsonweed junkies”, going from one Datura flower to another for their next fix, thus being manipulated by their pusher-plant to promote cross-pollination. Datura wrightii is native to the deserts of the southwestern US and Mexico, though it has escaped from cultivation or appears as a waif as far away as Washington State. American artist Georgia O’Keefe frequently incorporated Datura into her iconic paintings of the southwest (her most famous rendering of the species hangs in a museum in Indiana and is valued at 44 million dollars). Datura wrightii is also noteworthy for having the largest flowers of any native western US plant, with its white, funnel-shaped flowers often reaching 8 inches in length. The specimen shown here was collected by former WSU Postdoctoral student Mark Fishbein and associates on a collecting expedition to Baja California in 1998. The Ownbey Herbarium has specimens from over 80 countries around the world, with Mexico having the third most collections, after the US and Canada. For more information on the Ownbey Herbarium, go to https://ownbeyherbarium.weebly.com/ – Walter Fertig, collections manager, Marion Ownbey Herbarium. 1. Constance’s sedge (Carex constanceana)

On the morning of August 9, 1909, pioneer Washington botanist Wilhelm Suksdorf set out from his usual camp on the southeast slopes of Mount Paddo (now Mount Adams) to collect samples of the local flora for his personal herbarium and to sell to herbaria elsewhere in Europe and North America. On the talus slopes above Hellroaring Canyon, Suksdorf found a tufted sedge with stems 10-20 inches tall and clusters of tawny and green sac-like flowers. Suksdorf did not know it at the time, but he would be the last person to see this sedge alive. Though he thought it was the widespread Liddon sedge (Carex petasata), Suksdorf’s collection would become the type specimen of a new species named by John W. Stacey, an amateur botanist from San Francisco. Stacey noticed that the Mount Paddo plants had shorter and narrower floral scales than C. petasata, and more flower spikes and channeled leaves than Davy’s sedge (C. davyi) from California. “Constanceana” commemorated Lincoln Constance, an expert on the parsley and waterleaf families from the University of California at Berkeley, who started his professional career as curator of the Washington State University herbarium in the mid 1930s. Unfortunately, no botanists have been able to relocate Suksdorf’s population on Mount Adams, and this species is now thought to be extirpated in Washington. David Biek and Susan McDougall, authors of The Flora of Mount Adams, Washington, suggest that heavy sheep grazing in the 1920s and 1930s may have been the downfall of this edible, grass-like plant. The species was synonymized under C. petasata in the Flora of the Pacific Northwest in the 1960s, but later resurrected by Joy Mastrogiuseppe, former collections manager of the Marion Ownbey Herbarium, in the Carex treatment for the Flora of North America. More recently, geneticists have demonstrated that C. constanceana and C. davyi are the same taxon, with davyi being the older and accepted name. So, C. constanceana is gone again (taxonomically speaking), though intrepid botanists exploring Mount Adams should still keep their eyes out for it. Regardless of its Latin name, this is one of Washington’s rarest plant species. – Walter Fertig, collections manager, Marion Ownbey Herbarium.

3 Comments

Lynn Kinter

4/19/2024 06:50:35 pm

Thanks! These are very interesting blogs!

Reply

Laura Fertig

4/30/2024 05:30:12 pm

You've outdone yourself with this post! It's nice to see the insects get a shout out.

Reply

Al Kisner

5/5/2024 08:00:53 pm

Good job Walter. Very interesting to read.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorDr. Walter Fertig is the Collections Manager for the Marion Ownbey Herbarium. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed